Stefan Szczelkun: 'The End of British Democracy: What We Can Learn from the Penguin Story'

We had nearly 100 years of British Democracy with universal suffrage. Now we are facing the probability that it may end in a few years, around about its centenary if Reform get in. They are odds on to do that. People compare our predicament to the Thirties in Germany and other part of Europe. But why did Britain not fall in with the authoritarian and fascist surge in the Thirties?

One reason we kept our democracy was, I believe, the phenomena of Penguin Books. By the Thirties the vast majority could read because of universal state education. A young lower-class publisher realised that conditions were right to enable low-cost, but good quality, reading matter to be sold to this public. Up until then new books were too expensive for the majority of people. Literature and academic excellence were really only intended for an elite. Cheap editions and chapbooks existed but they were poorly produced and tatty. Penguins editions stood out as a quality product but were sold for just six pence each in Woolworths. They were well-designed, well-edited and carefully chosen to be the best writing. By this time there was a vast amount of quality hardback publications selling at more than five times the price of a Penguin. The rights to reissue the best of these books in cheaper editions could easily be bought when the sales of the first edition hardbacks had fallen to a trickle. Books that had been critically acclaimed and sold a few thousand copies as hardbacks could be reprinted as paperbacks in tens of thousands of copies. The distinctive modern looking pocket Penguin books were an immediate success. The first ten books included titles like A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway and The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie - authors who are still household names.

In the first year from mid-1935, three million Penguins were sold, and by 1938 there were 180 titles in print. Allen Lane had worked his way up the publishing business learning the ropes with The Bodley Head Press, before he started the Penguin imprint. Looking back, we can see how this wide availability of quality books changed the intellectual self-esteem of the majority of the population. The traditional publishers had been against publishing cheap paperbacks, but Allen Lane was not only undeterred but bold in his choice of titles. He had a belief in the intellectual curiosity of the common man and women and instinctively knew what they would enjoy reading. This was something that the dons of the elite publishing world didn’t understand and even feared. Lane was relaxed about people making up their own mind. There was no danger of them being morally corrupted or ideologically incited by reading a book. The Penguin list implied a belief that a well-informed public could be trusted to make a wise political judgement.

From 1939, Penguins played a part in the war effort. It was understood that an optimistic future for the majority of people could be conveyed through well-chosen books. And more simply that literary ‘edu-tainment’ was good for morale. Written material could help motivate people to keep fighting in what was a prolonged and terrible war.

After the war the democratic mission of Penguin to feed progressive books to newly literate masses continued. Lane himself had been hit hard by the death of his favourite brother in combat. Allen’s two brothers and sister were close and as a family and had supported Lane in the Penguin enterprise. Penguin kept expanding. And by the Sixties Penguin had grown into a huge corporate business which was increasingly under pressure to obey the dictates of commerce to maximise profit. This was resisted by Lane and his editors, and was symbolised by them hanging on to the colour coded and abstract cover designs against the pressure from America to have more lurid colour paperback covers.

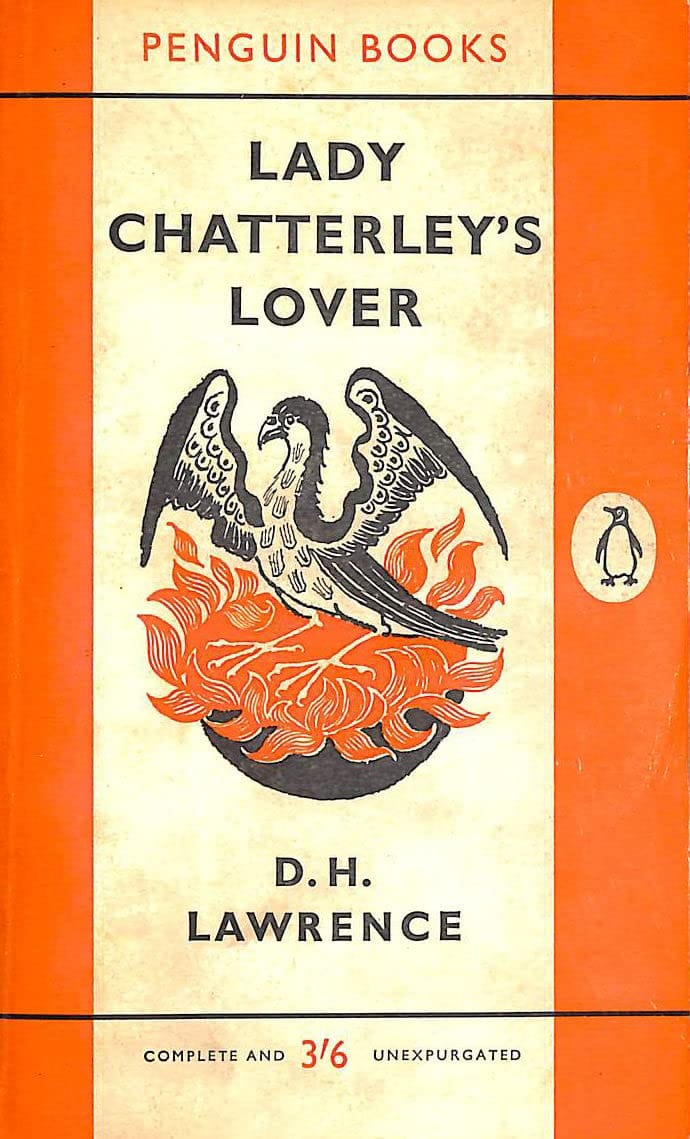

In 1960 Lane stood up against state censorship in a historic high court show trial over the censorship of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. With help from working-class allies like Richard Hoggart, he won the case against the stultifying good taste of the establishment. The Penguin edition of Lawrence’s novel went on to sell three million copies. At the trial, Lane is recorded as saying the idea behind his enterprise was:

“To produce a book which could sell for the price of ten cigarettes, which would give no excuse for anyone not being able to buy it, and would be the type of book which they would get it they had gone on to further education."

Allen Lane died in 1970 and Penguin was then bought by the corporate world. The altruistic mission of the Allen Lane project gradually became absorbed into mainstream publishing. The extent to which the original values of the Penguin imprint are alive is a matter of debate.

I have just read The Man Who Changed the Way We Read by Jeremy Lewis (2025 Penguin edition). This allowed me to appreciate that Penguins were a massive and transformative contribution to the intellectual life of working-class people from 1935 to 1970. It seems to me that this has not occurred in the same way following the mass entry into universities. Why this is not the case is a complex debate for another time, but for now I will say that a university degree may sadly divide working-class intellectual life as much as embolden it.

Jeremy Lewis’s book is supremely detailed, but it includes only a very light class analysis. As a result, it overlooks important context, such as the proletarian writers’ movements in the US and Britain during the Thirties. I came away with little sense of how many Penguin authors were working-class. One was Walter Greenwood, whose Love on the Dole (1933) was, perhaps by chance, one of my first paperbacks. Other Penguin authors Like Stan Barstow and Alan Sillitoe became known to me because of film and TV adaptations of their books. Working-class women were represented on the Penguin list by Ethel Mannin, Shelagh Delaney, Catherine Cookson, and later arrivals Ethel Carnie Holdsworth and Buchi Emechetea. Some non-fiction on working-class women’s lives was published in Pelican or Penguin Specials.

“Word people weren’t engaged in a process any more otherworldly than what transpired at the factory or the stockyard.”

- Mike Gold referenced by Devin Thomas O’Shea in a Jacobin article on Thirties US Proletarian writers, Feb 2026

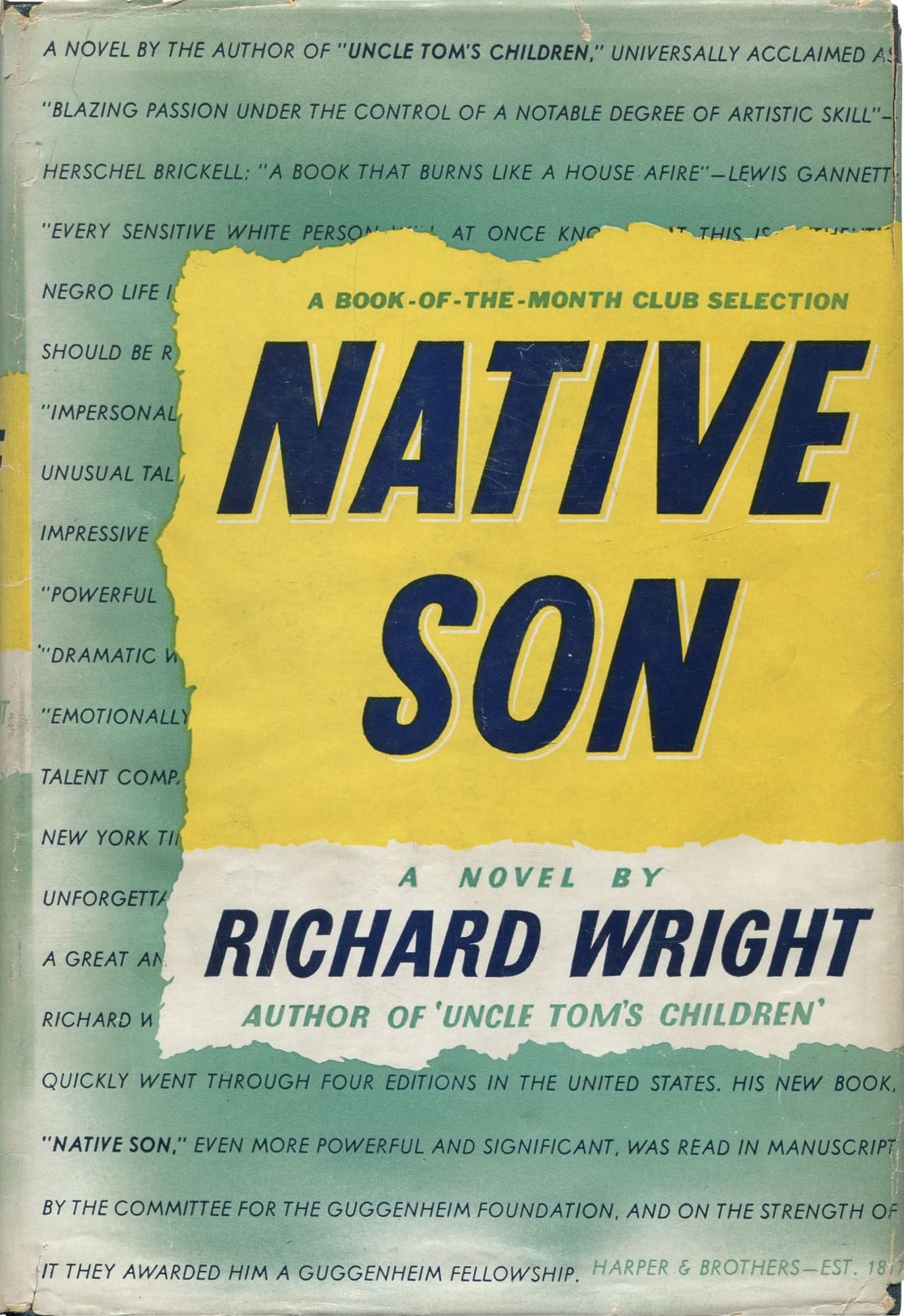

US black writer Richard Wright (1908 - 1960) was an important globalising influence on Penguin. His Native Son (Penguin, 1940) tackled racial conflict head on. In time this was followed by James Baldwin’s Go Tell It On the Mountain and Notes of a Native Son in 1963, which contains a trenchant critique of Wright and earlier social realist novels.

It’s hard to imagine what could be done now that could have a similar energising effect on the general intellect, especially on the scale that it occurred with Penguins. It would have to be bold and dramatic to escape the stultifying effect of systemic forces. We had hoped that the promise of the mobile phone and world wide web would result in a similar opening of knowledge, along with an access of all to debate and self-expression on global platforms. This has sadly not been the case except in certain projects like Wikipedia and the Internet Archive, which were set up to be resistant to commercial forces. Popular newer platforms like Substack and TikTok seem to encourage an individualisation of expression.

It would have to be an explosive flowering of working-class cultures in all ethnic variants and media. It would have to be regional and decentralised. It would have to be non-commercial and driven by enthusiasm. Such a movement would likely engage only minimally with algorithm-mediated social media, and would instead involve a strong emphasis on live performance, collective exchange, and sustained critical debate.

Allen Lane himself is probably not a model that could be held up for emulation by future generations. His modus operandi was the liberal use of alcohol to lubricate networking across class lines in the establishment. The cocktail parties worked but probably contributed to the colon cancer that killed him. Also, his early history, namely of how he came into the position to start Penguin, was just too quirky and one off.

At the moment, I can’t see many people who express the view that working-class intellectual culture is an essential component in the defence of a rational and inclusive democracy. Working-class ‘culture’ is too often represented as ending with drinking, cars and sport, if it has any meanings at all. Coming together in crowds is important, but there is too much embarrassment about informed critical discussion that goes beyond these subject areas.

The core stereotype of class oppression that we working-class people ‘don’t think as well’ as the Oxbridge types is still internalised and not widely contradicted. There are initiatives like the 93% Club that are changing the stereotypes about those of us who are the products of state education. There is also the Alliance for Working Class Academics - see here.

I’m reminded of mobile and militant cultural forms from the Seventies: Cinema Action projecting films of current events onto factory walls to ‘trigger’ discussion., and of 7:84 company’s agit-prop street theatre that engaged with local and global issues.

It will take bold actions to stem the current tide of English fascism! As a discussion point I’d make three linked suggestions:

- A transfer of wealth from the richest oligarchs operating in our media and markets, who are currently avoiding tax, to the poorest regions of the UK in ways that the redistribution is felt on the ground by families rather than absorbed by a managerial class.

- A cultural shift that re-organises cultural initiatives in these same areas from the ground up. This would mean using spaces currently attached to public libraries, adult education spaces, schools, youth clubs and working people’s clubs, pubs, clinics and hospitals, prisons etc, that will show artwork, performances and projects by working-class artists, including ‘politicised’ work, and that these events would be taken ‘into the communities’ to invite critical engagement. Artists would therefore need to be employed to work in person and in sustained, locally tailored ways, responding to specific histories and concerns. Such engagement should include feedback loops so organisers can learn from participants and adapt future provision to reach all parts of these communities. The cultural provision should avoid existing hierarchies of media expression and make a clear break with existing cultural managers and models from high culture. It should be inclusive, led locally and maintain high expectations of intellectual engagement. Perhaps this is where those working-class university graduates come in. The Mass Observation project offers one historical example of how such participatory cultural work might function. (See Penguin Special, Britain 1939)

- There are other inspiring localised initiatives that have come to my attention recently that are not primarily ‘cultural’: projects delivering food to those in need, free classes teaching basic healthy cooking, businesses that employ newly released prisoners while providing the support needed to rebuild their lives, and programmes assisting people leaving the armed services or struggling with addiction. All these and more need to be encouraged in the same way. They can also be work placements for artists to qualify for artists universal benefit. I’m imagining a musician playing while people eat in the community café and then helping with the washing up.

Stefan Szczelkun studied architecture in the late Sixties before realising he wanted to be an artist. He then engaged in a long process of self-discovery of what it meant to be a second generation Polish immigrant and a working-class person who wanted to work in a middle-class profession. In the process of his explorations he took part in a series of artists collectives. Realising that these exciting groups were not in the books on art history he decided to do a doctoral study of the group he was currently part of - Exploding Cinema. He completed his PhD at the Royal College of Art in 2002 and was working at Westminster University until his recent retirement.