Hendry Tan: Delaying Calamity, an Exploration of Dissonance and the Attempts to Co-Exist

Writing and photographs by Hendry Tan

Delaying Calamity explores the realm where natural and artificial go beyond coexistence and descend into calamity. Humankind’s collective, forced imposition of artificial tools has reached its tipping point - creating dissonance, catastrophe, and death. This visual documentation takes place in Pakistan, where the coexistence of nature and tragedy is stark.

In Pakistan, nearly everyone relies on the mighty Indus River, stretching from the

Himalayas to the Arabian sea. However, climate change has ravaged the Indus with catastrophic floods, while another, quieter threat has brought silent deaths: pollution. Pollution in the Indus has caused severe drinking water contamination - from industrial, agricultural, and faecal discharges - resulting in farm animal deaths, annual outbreaks of cholera and long-lasting intestinal parasites among the people. The presence of harmful chemicals, heavy metals, and bacteria in the water contributes to skin conditions such as tinea corporis, folliculitis, and eczema, as well as eye infections like conjunctivitis. Contaminated water alone has caused 97,900 human deaths annually, 54,000 of whom are children under five.

However, my project not only highlights this tragedy but also documents the brave individuals working to reverse the catastrophe and prevent further harm. Together, they strive to restore balance through free healthcare, sustainable agriculture, and accessible education - so that the natural and artificial can finally coexist.

Meet the team from the Karachi-based NGO Vision Healthcare Foundation, led by two childhood friends; renowned ophthalmologist Dr Mazhar Awan, and Justice Retired Supreme Court of Pakistan, Mushir Alam. I joined a group of doctors from Khairun-Nisa Hospital, organised by the kind and quick-witted Ahmed Ali, to visit two locations: Khokhrapar, a pastoral community in Karachi’s Malir district, and Mubarak, a village roughly 60 kilometres outside the city. Our mission was to distribute free eye care to these underprivileged communities.

Awareness of eye health is very low among many Pakistanis, particularly those in rural areas, which make up over half of the population. In these communities, limited access to clean water has led to a rise in conjunctivitis cases, in addition to common conditions such as cataracts and refractive errors.

The team is more than just a group of experts on a field mission. Ahmed Ali, Tabinda Hanif, and Asfand Hussain have become especially dear friends, and I feel equally close to Ammara Zafar, Masood Ahmed, Jasim Ghafar, Ayesha Barkat, Hira Mansoor, as well as Ali, Rayan, and everyone from the Humanity Initiative team - and, of course, our trusted driver, Albert. It is the camaraderie, built on shared warmth and mutual respect, that enables this group to thrive anywhere, no matter how challenging the circumstances.

Camaraderie is essential for genuine human connection. In an age where artificial tools often overshadow face-to-face interactions, many of us tend to isolate ourselves. This raises an important question: how far are we willing to go to treat others like family? Perhaps, in this unstable environment, Pakistanis understand the true essence of camaraderie better than anyone.

During my time in Hyderabad, Pakistan, I was treated to otherworldly hospitality by the Soomro tribe. The Soomros established the Soomra Dynasty in the early eleventh century. And in the twenty-first century, they are setting an example for how we should treat everyone - with love and respect.

However, among all this natural beauty, there is tragedy lurking a few steps away - the Indus. The locals can’t do much. Though they protest - either about the neglected road, the rapid soil degradation due to unmanaged garbage that terrorises many neighbourhoods, or the toxic state of the Indus that kills livestock and everyone's livelihoods - nothing seems to have changed.

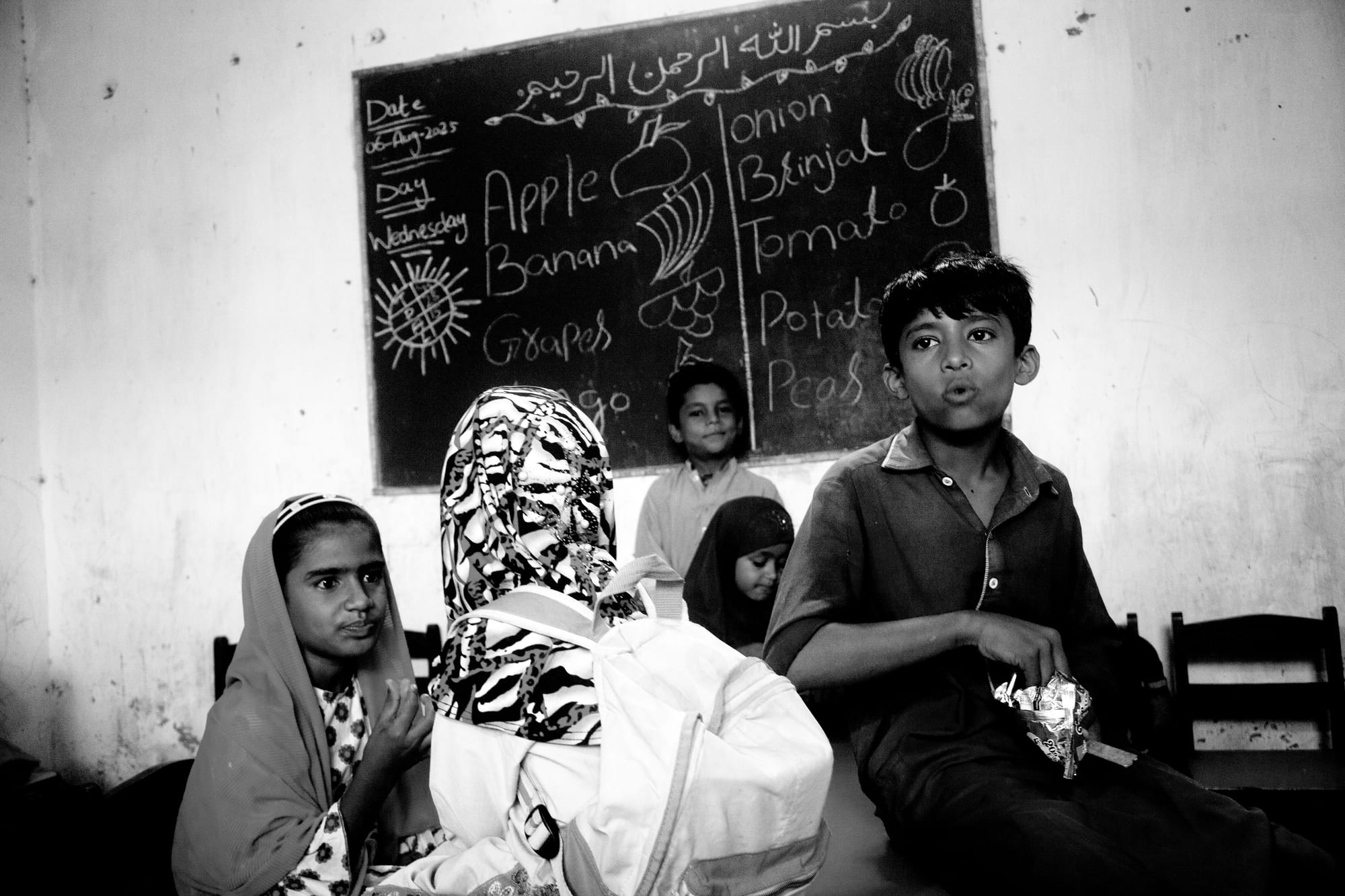

But there is one community south of Hyderabad that is pioneering change. These are the Khoso tribe. They understood that change has to come from within. They emphasise the importance of education from a very young age, both about Islam and general academic subjects such as maths, history, and language.

The Indus flows from the Himalayas all the way to the Arabian Sea at the Indus Delta, carrying pollutants along its entire course. Added to these are sewage discharges from nearby neighbourhoods, further contaminating the river.

The delta itself is home to a very rich marine life. One fishing village named Ibrahim Hyderi, believed to be one of the first settlements that established modern Karachi, is still bustling with wooden boats docked on its port. With open markets that last from morning until late afternoon, it is the main destination for locals looking for fresh, cheap fish, prawns and crabs.

The shores were scorching hot. Karachi itself has been experiencing a series of heat waves that go all the way to 45° Celsius, typically in the months of March all the way to June and July. Climate change, along with rapid urbanisation, deforestation, and heat-retaining infrastructure make Karachi hotter than its surrounding areas.

Karachi’s coastal location used to provide some relief through sea breeze. But with changing wind patterns and ocean temperatures, sea breezes are weakening, and hot inland winds dominate more frequently. There is also an increase in humidity due to climate change, making it harder for the body to cool down through sweat. Moreover, it has been made worse by the constant daily power cuts happening all over the city, turning fans and air conditioners into mere decorations. More and more people are shifting toward solar panels, of varying qualities and prices, all imported from China.

Life hasn’t been kind to the underprivileged in Karachi. Many neighbourhoods are still struggling with insurmountable amounts of trash piling up on the sidewalks, such as a neighbourhood in Mehran Town, Karachi, where uneven dirt roads dominate. Some are also experiencing uneven distribution of education.

However, Ahmed Ali - affectionately known as Ahmed Bhai (“brother”) - the driving force behind many VHC healthcare missions, is working to create change through the establishment of the Shining Star Foundation. At the heart of Mehran Town, the foundation has opened a primary school that provides free education to underprivileged and underrepresented children.

One year ago, Ahmed Ali’s father passed away. His wish was to open a school for the less fortunate. From that, Shining Star was born. Along with his brother Suleman Wahab, and his son, Muhammad Akleem, they run the school in between their hospital and university duties. It was not an easy task to begin with, but Ahmed Bhai stands tall and determined, working to bring meaningful change to these children’s lives.

These brave, resilient, sincere, caring, and humble individuals are at the core of Delaying Calamity. These are the people who will always be here, no matter how tough the circumstances, or how doubtful those on the opposite side of the current may become. Because every smile from an elderly woman with cataracts after a successful surgery, every household sharing stories over a clean meal with vegetables grown at a nearby farm, and every laugh of a child playing with classmates instead of doing gruelling hard labour tells a story of hope and the goodness of humankind. These brave people are the voice of the marginalised.

Hendry Tan is a documentary photographer based between Karachi and Jakarta.