Mermaids and Cowboys: In Conversation with Elif Yilmazturk

Elif Yilmazturk is a British self-taught artist based in Surrey where she lives and works from her cabin. Known for her oil paintings, charcoal drawings, and original works on paper, her art blends elements of folklore, storytelling, and historical themes, creating a mood that is both dreamlike and ethereal. GRASS editor, Tommy Sissons sat down for a chat with Elif ahead of the launch of Issue 5.

T: What inspired you to create art, in terms of influences from your personal life and the artistic world?

E: It’s a funny one because there’s so many things that I look at whether it’s fashion, film, music or art itself, but a lot of my inspiration comes from fashion and film rather than paintings. People always ask me about paintings I love – I do know paintings, but I have more of a reference in film and fashion and mood – my own mood.

I struggle with mental health. I have quite a lot of anxiety and depression which has gotten worse over the years, so I think that comes out a lot in my work. It’s very moody. Haunting. Melancholic. I didn’t even realise I do it.

T: The work is therapeutic in a way?

E: Very therapeutic! Sometimes I worry because people say, you know – art therapy, but I get worse as I paint sometimes.

T: Because it’s an act of facing /

E: Facing what you’re dealing with, a little bit. Yeah. You think, oh there’s some real darkness there that I didn’t realise there was.

T: So, it’s an act of getting to know yourself better, even these sides of yourself that you struggle with.

E: It’s funny, because naturally when people meet me, they think I’m quite bubbly, but I’ve also got this dark, serious element to myself. Very Gemini. I’m not a Gemini though. I'm a Scorpio. Makes sense. If anyone’s into horoscopes they’ll go: It makes sense!

T: Where does your art emerge from? What’s your personal relationship with it? How does it relate to the world today and/or to your native south London?

E: In terms of London, I do love a lot of English history. I love Medieval art and the 1500’s and 1600’s royalty – all those paintings by [Hans] Holbein [the Younger]. South London not so much, but if we’re talking about London heritage, I love the Medieval and Renaissance periods, which I think comes out in my work. Very ethereal vibes. What would be south London? Now I’m intrigued.

T: I’m counting Sutton as south London. Well, it’s subjective. It could be that you have some sort of relationship with Sutton and a broader sense of 'home' which might communicate itself through your work subconsciously. Maybe you don’t. Maybe the work is complete escapism from that.

E: Maybe!

T: In which case, it’s still related to the experience of south London because it’s an escape from that.

E: I’m thinking of south London for the last like forty years. Street style. It’s very not me. I feel like I’m from a different time. I just kind of wanna prance around in a massive dress and at the same time I’m such a feminist, I probably wouldn’t do well [in the Renaissance or Medieval period].

T: Where do you create?

E: I used to have a little garden studio. There’s a room in my parents’ house that I’ve now made the art room. Unfortunately, I find it really difficult to paint in my designated art space meaning I end up bring art materials to my bedroom. I want to go into my safe space, my bedroom. I don’t know why.

T: I think that’s quite a natural thing to do.

E: I see it as therapeutic maybe. An enjoyment area. I’m bringing it there. When I bring it to an art space I go into work mind, then I get stressed.

T: If the work is intimate to you, then you want to be in a setting which is reflective of that.

E: Yeah, and I think when you put pressure on yourself as a creative it gets dangerous. You’re at your best when you’re really feeling the work and that’s very hard to come by all the time, naturally. If you could push out art all the time, great. But I don’t know if that’s natural. I have little moments where everything’s amazing and I’m understanding it all and then I have moments where I need to not paint. I need to soak up the world around me to be inspired again.

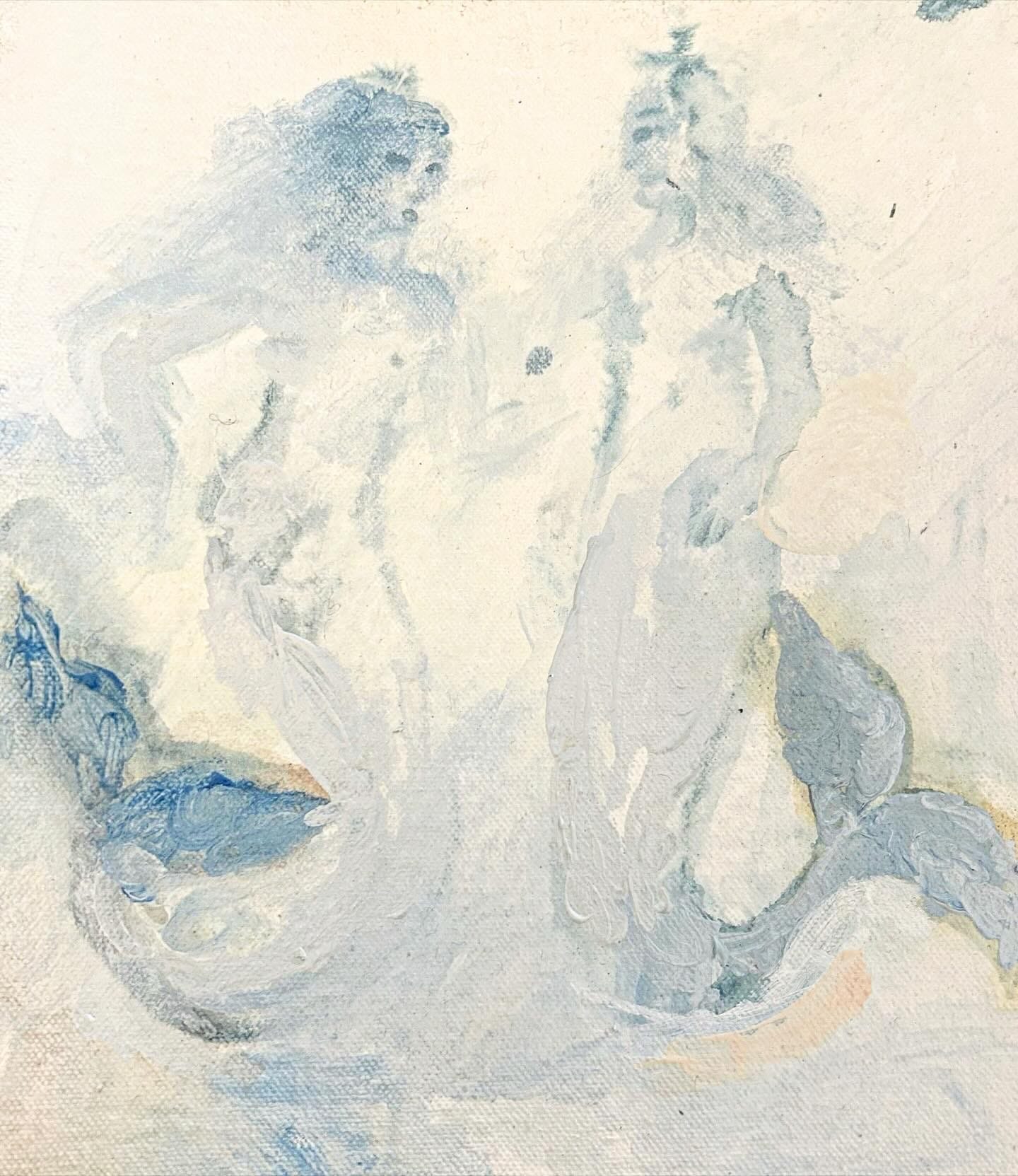

T: You said recently that you prefer work which is ‘incomplete’. Why is this? As this is an aesthetic in itself, how does this aesthetic speak to/represent your work and its distinctiveness?

E: I prefer my own work when it’s half-completed. I love the idea of things being there and not being there. That’s why my work gives off ghostly vibes. And I love the rawness of a sketch and how delicate it is. When it’s effortless. I don’t like completion.

T: A lot of art resists this idea of perfection, right?

E: Right, and I read somewhere ‘a great artist knows when to stop’. I’ve ruined paintings before where you just keep going and I think it was perfect before.

T: How do you know when a piece is complete?

E: I try not to get opinions from other people. When I know someone’s given an opinion on something I’m like ‘now I can’t fricking touch it’, and it doesn’t feel good to me. I just know. I look at it and love it. Sometimes I take a photo of it and look at the photo. It feels like I can see it better.

T: It’s a different lens through which to see something. You see the completeness of it as if you were an observer and not yourself, looking at it through a phone which is how a lot of people now consume art?

E: Yeah. And I can walk away from it. I do the catwalk of walking away, then turning my head and looking at it from a different angle. Then I get frustrated, leave for twenty-four hours, come back and realise it is quite good. It’s dangerous to over-look at something. It’s a bit like body dysmorphia. If you look at your face for too long all of a sudden, your face is getting warped, and you forget what you’re staring at. You need little breaks. Your eyes play tricks on you. I know when I know. Which is never.

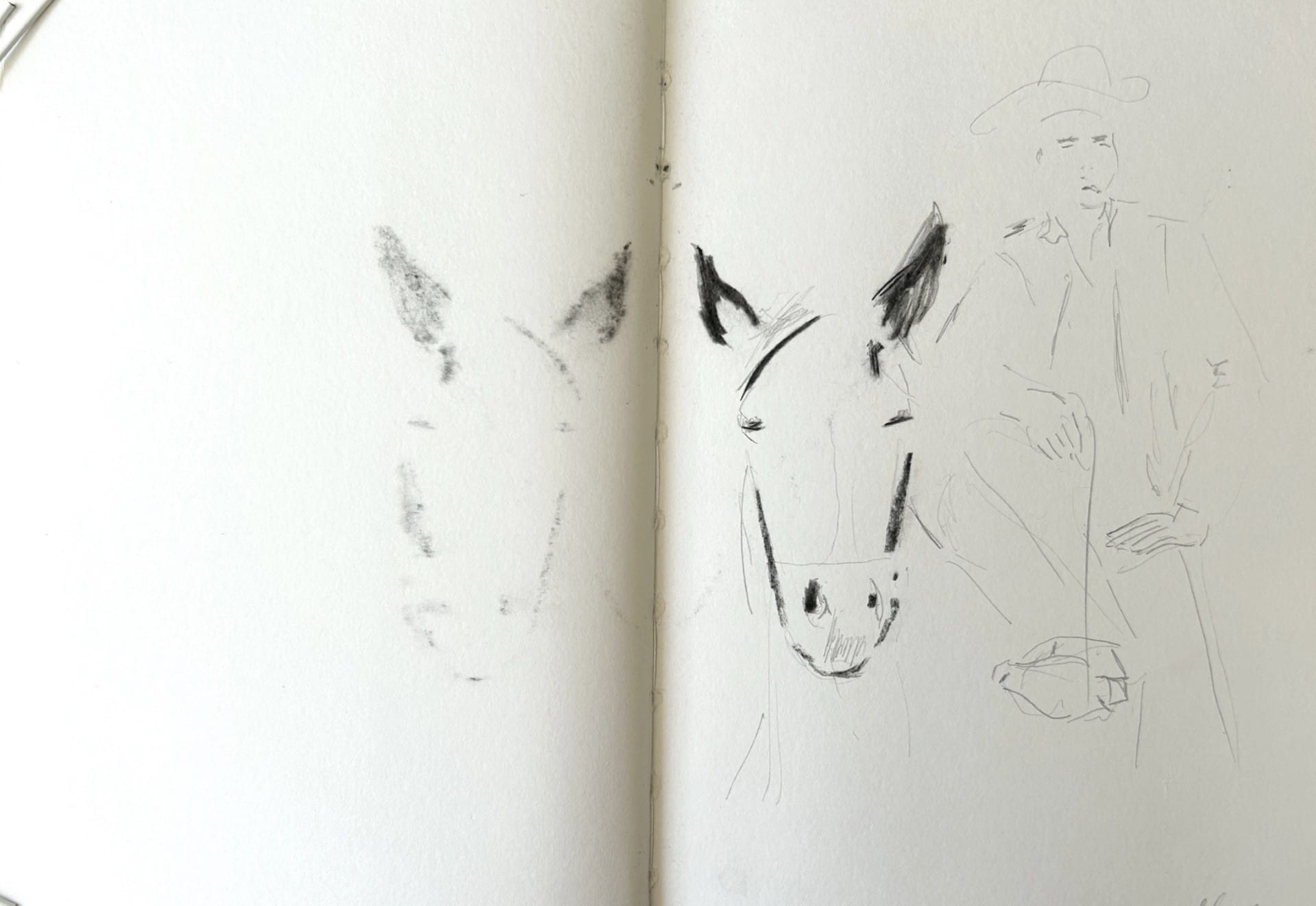

T: You use the figure of cowboys in some of your pieces. Why is this? The cowboy’s an archetypical outlaw figure. To what extent does the figure of the outsider or rebel relate your artistic practise?

E: You’ve nailed it, I think, in that question. At one point I was loving 1960’s Western films. My dad introduced me to them. a lot of imagery from those films. I love the rawness of the cowboy working, the farming aspect of it. Which is ironic, because I also love the pompous ceremony of Medieval kings and queens. But I do love the outlaw, rebel badness of it. I don’t know why; not yet to discover it.

T: There’s a bit of pompous ceremony to the cowboy.

E: A little bit. It’s a bit chauvinistic, isn’t it?

T: Yeah, but also the uniform of it. The uniform speaks for the character. Visual metonymy. You see the cowboy outfit and you think of that. And the kings and queens /

E: They’re all visual led in the way that they act and dress.

T: Why mermaids?

E: I think mermaids are the idea of these women – sirens – who are going against society. They’re mystical creatures that women love. They’re very dangerous. And I’ve met some women in my life who are very dangerous. There’s something interesting about a dangerous woman – not that I am a dangerous woman, maybe I am – it’s the idea of the siren. These beautiful women leading men to their deaths. I’m very much into fantasy and fairytales and I prefer fantasy to reality.

T: I can see there being a psychedelic ‘60’s/70’s and also a cinematic element to your art.

E: Yeah, I listen to music when I paint. Rock and Roll. Soundtracks. The 1960’s where everyone was taking acid and listening to those songs, there’s not a lot of singing in it – it’s more instrumental with maybe someone singing in the background. If I listen to music that’s too 'singy' it distracts me too much. That’s why I like soundtracks or the 1960’s drug music, because you can zone out and get into the work.

T: How do you find the experience of being an artist in the UK in 2024?

E: Difficult. I know lots of people are struggling in their industries at the moment, post-pandemic. Whether that’s in film, fashion, they’re all taking hits. It’s very easy to slip into getting a bit dark about what you do. The thing is to just push on with it. What I do love about being an artist in 2024 is I do have social media to be a bigger platform for my work than any gallery could have been. I wasn’t born into an art family, so I don’t have any art contacts or anything so social media is how I was able to make contacts. Everyone has a love/hate relationship with social media but I’m so thankful for it at the same time.